Press Release

Reauthorizing the Pandemic and All-hazards Preparedness Act: strengthening the readiness of U.S. cities

April 2023

As major public health threats grow in number and severity, here is how our nation can prepare.

Updated September 2024

Big city health departments (including county departments that serve big cities) are on the front lines preventing and responding to public health emergencies, including natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and pandemics.

Public health preparedness at the state and local level gets funded primarily through federal cooperative agreements authorized in the Pandemic All-Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA).

Specifically, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) provide funding to 50 states, four localities (Chicago, Los Angeles Co., New York City, Washington, D.C.), and eight territories and freely associated states. Most local health departments receive funding through their states rather than directly from the federal government.

Local health departments help build resilient communities by preparing for these emergencies and supporting residents recovering from them. Funding authorized through PAHPA is critical to that lifesaving work.

The Big Cities Health Coalition therefore urges Congress to reauthorize PAHPA to enable health departments to prepare for future public health emergencies. Below, we outline the specific steps we recommend as part of this reauthorization.

Our priorities for PAHPA reauthorization

Prepare for a timelier emergency response: Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreements

The PHEP grant program, administered by CDC, was created after September 11, 2001, to provide core funding to strengthen local and state public health departments’ ability to respond to public health emergencies, including terrorist threats, infectious disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological emergencies.

As we have seen during the pandemic, public health emergencies have the power to cause large-scale human and economic losses. The U.S. needs stronger local, state, federal, and territorial public health agencies able to protect the health of all Americans in the face of 21st century threats.

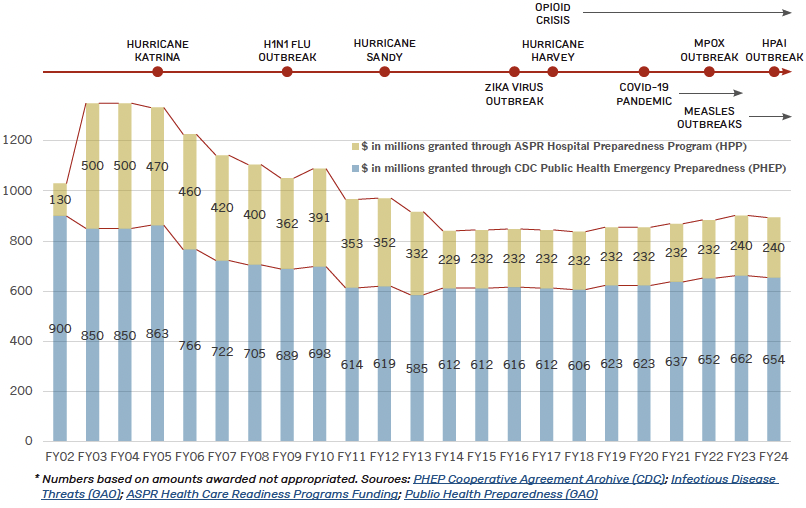

Fig. 1 – Despite a sharp increase in severe public health emergencies, preparedness funding has plummeted 34% since 2003.*

* Based on amounts awarded not appropriated. Sources:

PHEP Cooperative Agreement Archive (CDC); Infectious Disease Threats (GAO); ASPR Health Care Readiness Programs Funding; Public Health Preparedness (GAO)

Press Release

BCHC Vice Chair urges Congress to reauthorize PAHPA

This amount accounts for inflation and aligns it with the intended 2002 buying power of $1.08 billion. PHEP funding has been cut by nearly 34% over the last two decades, despite the increase in emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, and weather-related, environmental, and other emergencies and disasters. The continuous barrage of wide-scale public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and mpox, demonstrates the need to reauthorize and reinvest in these programs to rebuild and bolster our country’s public health preparedness and response capabilities. The graph above illustrates the sharp drop in preparedness funding, even as severe public health emergencies have increased in frequency and severity.

Congress should request a Governmental Accountability Office (GAO) report examining how states determine the appropriate portion of PHEP awards for local health departments and make recommendations on how these funds can be more efficiently used to support systemwide preparedness.

Ensure health care systems are ready: Fund Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) cooperative agreements

HPP, administered by ASPR, prepares the nation’s health care system to save lives during emergencies and disasters. HPP supports regional health care coalitions to incentivize readiness, assess risks and needs, train the workforce, and maintain preparedness among organizations that might otherwise see each other as competitors.

ASPR data show that 96% of participating hospitals say HPP support has improved their ability to decrease morbidity and mortality during disasters. Despite this, HPP has been cut by more than 50% over the last 20 years.

This is the amount grantees received 20 years ago in FY 2003. See the graph above for the sharp drop in preparedness funding, even as severe public health emergencies have increased in frequency and severity.

Speed up response times: The Public Health Emergency Fund (PHEF)

Emergency dollars are critical to support a robust response in the intervening time it takes Congress to act. Big cities are often first to respond to crises and must use whatever dollars are available at that moment, with the expectation that the federal government will contribute later to the response.

For example, in the 2016 Zika outbreak it took Congress more than 200 days to respond to an emergency request from the Obama Administration. A mechanism to get dollars out quickly to local, state, and federal public health agencies is critical for standing up an emergency response in a timely manner – and therefore critical to saving lives.

Reauthorizing the PHEF would reinstate a method to quickly provide money to the HHS Secretary as well as to state and local partners. Such funds should be additive, not require jurisdictions to use existing preparedness funds, and should also not rely on CDC to use their own response fund which is primarily used to support internal activities.

The PHEF needs a trigger mechanism whereby it receives an immediate infusion of resources once a public health emergency is declared.

More shots in arms: Strengthening adult vaccine infrastructure

The COVID-19 pandemic taught us that we need a comprehensive vaccine infrastructure to immunize all Americans against infectious disease threats. This infrastructure enables future pandemic response, while also ensuring access to routine vaccines in non-emergencies.

The National Vaccine Program or 317 is essential, but it is not sufficiently funded to support vaccination for all uninsured adults. Even with improvements in access to adult vaccines in Medicare Part D, Medicaid, and CHIP, significant gaps in coverage and infrastructure for adults still exist.

Authorizing a Vaccines for Adults program – or providing sufficient resources to expand the 317 program – would support un- and under-insured adults’ access to Advisory Committee on Immunization practices (ACIP)-recommended routine and outbreak vaccines at no cost.

Deliver funds quickly where they are needed most: Increase flexibility of grants to state and local public health agencies

Effective public health response depends on action at the federal, state, tribal, local, and territorial (STLT) levels of government. As CDC supports STLT readiness and response, it needs explicit authority to direct funding to agencies at all levels of government.

Any such authority should also include analyzing the efficiency and efficacy of how states deliver federal funds to localities.

Whenever possible, CDC should broaden its grantmaking pool to include, at minimum, the 107 jurisdictions funded under the Public Health Infrastructure and Grant Program. These grantees includes 50 states and Washington, D.C., as well as eight territories/freely associated states, and 48 local health departments that serve either cities with a population of at least 400,000 or counties with a population of at least 2,000,000 (based on the most recent U.S. Census).

Health departments need multi-year funding awards with 24-month budget periods and the ability to redirect funds during the budget period. This would reduce the administrative burden of processing carryover and no-cost extension requests.

A quicker, more precise emergency response: Modernize public health data

CDC needs the authority to collect and coordinate the public health data necessary to serve its mission and address known blind spots. The current framework for collecting and sharing public health data has resulted in fragmented and inconsistent reporting to CDC, and to state and local public health partners.

Expanded data authority for CDC will allow for more complete and timely data sharing to support decisions at the federal, state, and local levels, while reducing burden on providers. Every effort must be made to strengthen public health data systems as an essential component of emergency preparedness.

Congress should provide CDC with the authority to require reporting of minimum necessary data to serve a range of public health and other mission-critical use cases.

Including the Improving Data Accessibility Through Advancements in Public Health Act or Improving DATA in Public Health Act (H.R. 3791 / S. 3545) promotes coordination between federal agencies to share critical public health data used to prepare for and respond to public health emergencies. The bill also creates standards to improve and secure the transfer of electronic health information and establishes an Advisory Committee to ensure that public health data reporting processes are carried out effectively.

Nimble in an emergency: Temporary reassignment of federally funded staff

Currently, only governors and tribal leaders are authorized to submit temporary reassignment requests to support a public health emergency. BCHC supports reauthorizing temporary reassignment of federally funded staff in an emergency and urges modification to the provision to provide flexibility so local health departments and federal agencies may also issue and receive temporary reassignments. Expanding that mechanism would enable increased continuity of operations that are vital for a response.

Congress should direct HHS to work with its agencies to establish a “one-stop shop” for STLT health agencies to submit emergency reassignment requests. STLT health agencies should not need to repeat the entire process each time the public health agency renews an employee.

Change the language to allow Public Health Emergency Preparedness directors to submit the request on behalf of the jurisdictions directly to ASPR, not via an elected official.

Get this brief as a PDF

Download now Get this brief as a PDFQuestions about the priorities outlined in this document?

Contact Chrissie Juliano, Executive Director, Big Cities Health Coalition