Frontline Blog

Why we need an Urban Health Agenda for big cities

June 2022

Urban health is expansive and interconnected. It encompasses the interdependence of many social conditions and physical structures. Ultimately, these factors impact how long and how well we live. Our Urban Health Agenda highlights this interdependence and can help city departments align these factors to create and sustain health.

Urban health is influenced by both physical and human infrastructure.

Physical infrastructure includes elements like sidewalks that protect pedestrians, elderly, and disabled travelers on roads; grocery stores that provide healthy, affordable options; broadband that keeps people connected to emergency, or other social, services; and homes that keep people safe and sheltered.

Human infrastructure includes community-based non-profit organizations and other governmental and non-governmental agencies that provide assistance to elders, children, and people who are marginalized or who are in need of essential support.

Health is not created within the health sector. Health is impacted by the conditions of people’s lives.

Dr. Camara Jones, American epidemiologist, physician, and activist

How well the human infrastructure interacts with the physical infrastructure depends on organizational and sociocultural factors such as fiscal practices, social cohesion, racial bias, trust in government, and patterns of civic engagement. Each factor is interdependent and can influence the degree to which policy decisions undermine or promote urban health.

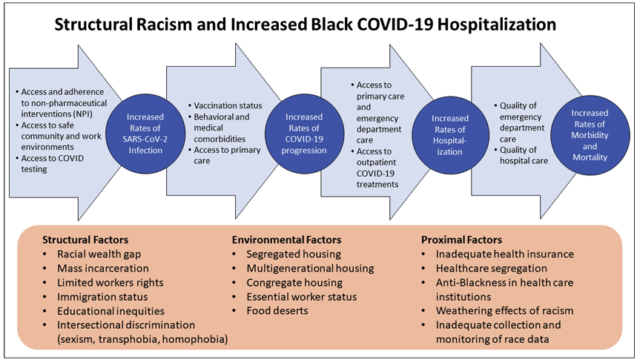

When health is undermined, the impact is disproportionately felt among people of color.

As big cities emerge from the acute response phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, one thing is clear: a community is only as healthy as the least healthy among it. Health is inexorably linked to every facet of our communities and the lives of the people who reside in them – including employment, housing, carceral status, and access to food, transportation, education, and health services. Racial and ethnic inequities and disparities in any of these facets of our lives ultimately undermine the health of everyone.

At the same time, we also see positive examples of how intertwined a community’s health is: Angela Glover Blackwell refers to the “curb cut effect,” which highlights how investing in one group (in this scenario, those in wheelchairs) affects the broader well-being of a community (making sidewalks more accessible for those pushing strollers, for example).[i]

Because no specific city department is charged with seeing and managing the “big picture” in big cities, public health departments often step in to navigate this role. By the nature of their work, public health professionals are ideally situated to highlight the interconnections between health and every aspect of urban life. While public health departments can catalyze efforts to create and improve health, they cannot do this work alone. To be successful, these efforts require partnerships and collaborations with all local government agencies, elected and appointed officials, and community-based organizations. Every department within city government bears some responsibility for urban health.

Case studies: The many environmental factors shaping urban health

[i] “Equity: Not a Zero-Sum Game”, by Angela Glover Blackwell, author of “Curb-Cut Effect”, published in Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2017. Via Policy Link.