Frontline Blog

Preventing the next outbreak: inside Austin’s measles readiness model

August 2025

When measles reemerged in the U.S. earlier this year, public health leaders in Austin didn’t wait for it to knock on their door. Instead, they asked: What if it happened here? And more importantly, how ready are we?

The result was a cutting-edge simulation tool that’s helping local officials anticipate and prevent a potential outbreak. It’s a clear example of how data-driven foresight, not just rapid response, is the gold standard in public health protection.

This isn’t just innovation for innovation’s sake; it’s life-saving work that could help cities prevent the next infectious disease crisis. And it’s a powerful example of why sustained federal investment in public health data systems is essential to protecting our communities.

In communities where vaccination rates dip even slightly, the risk of measles outbreaks rises dramatically. This new measles calculator puts that reality into stark relief, showing how fast measles can spread and making the invisible visible.

Desmar Walkes, MD, Public Health Authority for Austin-Travis County

A simulation tool built for action

After seeing a rise in measles outbreaks across the country, Austin officials wanted to better understand what could happen in their own backyard. In February, Austin Public Health’s Dr. Desmar Walkes, who is the public health authority for Austin–Travis County, began to gather a team to develop a tool. Drawing on experts from the University of Texas at Austin, CDC’s Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, epiEngage (a CDC-funded group focused on developing tools to improve public health preparedness) and other institutions, the team rapidly built and launched a simulation model to estimate the impact of a potential outbreak.

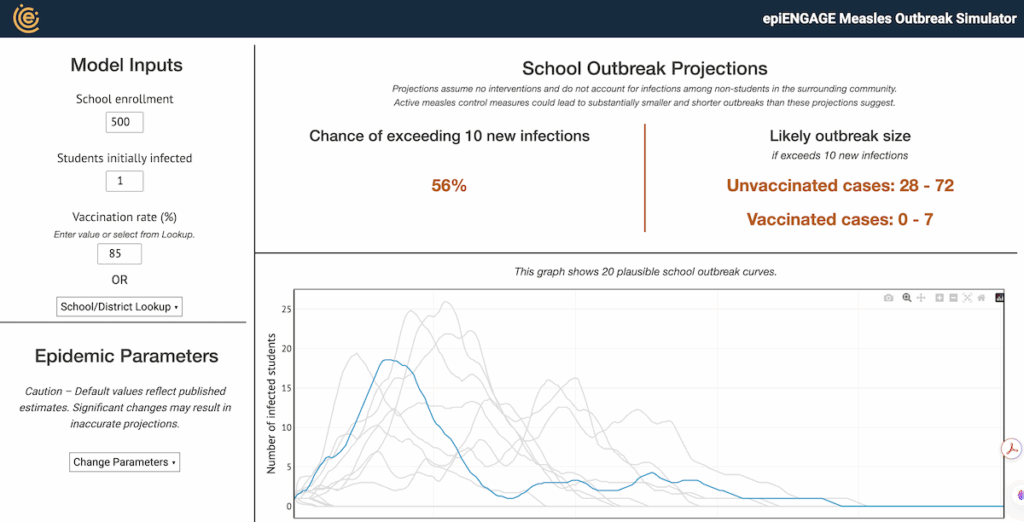

The epiEngage Measles Outbreak Simulator allows leaders to model hypothetical measles outbreaks by adjusting variables like vaccination coverage and population size. The results help estimate how many people could get sick, and how quickly, under different scenarios. Even without factoring in active public health response, the model gives cities a sobering glimpse of what could happen if vaccination rates continue to slip.

One big takeaway quickly became clear: small pockets of undervaccinated children can quickly lead to large-scale outbreaks. Vaccinating as many children as possible before an outbreak starts gives the whole community optimal protection.

Screenshot from the Measles Outbreak Simulator

From the cloud to the classroom

What makes the simulation tool particularly impressive is its speed and scope. It was built and launched in just a few weeks earlier this year and is already being used in Austin and other jurisdictions across Texas and the country. Illinois health officials have even replicated the model for their own use.

Austin also used the tool to engage local school districts, helping superintendents and principals understand where measles risks are highest and how the health department can support prevention efforts through vaccination outreach.

“In communities where vaccination rates dip even slightly, the risk of measles outbreaks rises dramatically,” says Dr. Walkes. “This new measles calculator puts that reality into stark relief, showing how fast measles can spread and making the invisible visible. It’s a vital tool that empowers schools, healthcare providers and families to act now, keep students safe and strengthen our collective immunity.”

This kind of real-time, collaborative public health work isn’t possible without strong data infrastructure and the capacity to analyze it.

The case for continued investment

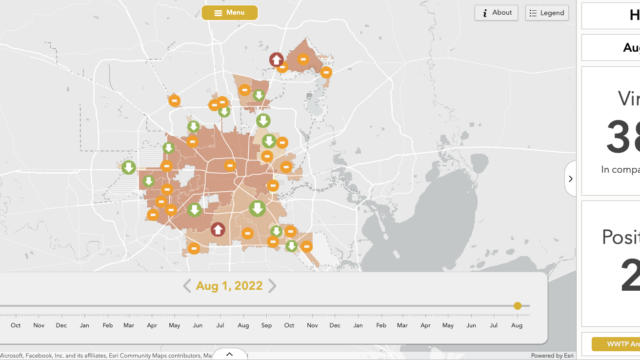

The measles simulation tool is part of Austin Public Health’s broader “Insight Net” effort, an initiative to make data-driven planning central to public health emergency preparedness. But like many such innovations, it’s not guaranteed to continue without sustained funding.

In recent months, health departments across the country have been facing cuts to federal grants that support data modernization and emergency readiness. These funds have enabled local departments to hire data experts, improve disease surveillance systems, and build tools like Austin’s measles simulator.

Without continued federal investment, we risk falling back into a reactive posture—responding to outbreaks after they’ve already taken hold. That’s not just inefficient; it’s dangerous.

Austin’s work shows us what’s possible when local health departments have the resources to plan ahead. They’ve transformed a looming threat into an opportunity to engage the public, inform decision-makers, and prevent illness before it happens. In a world where new outbreaks are always on the horizon, we can’t afford to do less.